Twice as many people think they have a food allergy than actually do1. This can lead to self-diagnosis, and premature elimination of food groups out of the fear that we, too, are allergic. Still, how do we know we have a true allergy? What’s the difference between an allergy and a food sensitivity? And how do we test for it? Here, we debunk common myths around allergies, sensitivities, and delve into how we can accurately test ourselves. Let’s learn how to find fact from fiction in the complex field of food allergies.

Increased awareness of, and access to, food allergy testing has led to record high levels of reported “food sensitivities”2. In turn, this has created widespread elimination of core food groups, which increase risk of nutrient deficiencies3 and undesirable microbiome alterations4. Whilst the terms “allergies”, “sensitivities” and “intolerances” are often used interchangeably, their meanings are distinct, and have different impacts on those affected. Therefore, it’s important to clarify the scale of severity in adverse food reactions, which ranges from mild sensitivity to true allergy. Correct categorisation is key for finding an appropriate treatment, as well as ensuring elimination of beneficial food products is only applied if necessary.

Whilst reported global food sensitivities have increased, defining the exact prevalence of true allergies remains rather difficult. This is because of how unreliable self-reporting can be, and since the grouping of sensitivities or intolerances as allergies further compounds the overestimation. Current estimations report between 1- 10 percent of children are affected worldwide5, with 14 main food products listed as potential ‘allergens’, indicating the scale of the issue. No wonder there’s so much confusion! Testing options range from hair analyses to Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody response – and many more in between. Here, we separate fact from fiction, to ensure that accurate diagnoses can be made, so that unnecessary and potentially harmful dietary restrictions can be prevented.

Whilst reported global food sensitivities have increased, defining the exact prevalence of true allergies remains rather difficult. This is because of how unreliable self-reporting can be, and since the grouping of sensitivities or intolerances as allergies further compounds the overestimation. Current estimations report between 1- 10 percent of children are affected worldwide5, with 14 main food products listed as potential ‘allergens’, indicating the scale of the issue. No wonder there’s so much confusion! Testing options range from hair analyses to Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody response – and many more in between. Here, we separate fact from fiction, to ensure that accurate diagnoses can be made, so that unnecessary and potentially harmful dietary restrictions can be prevented.

What Is a ‘True Allergy’?

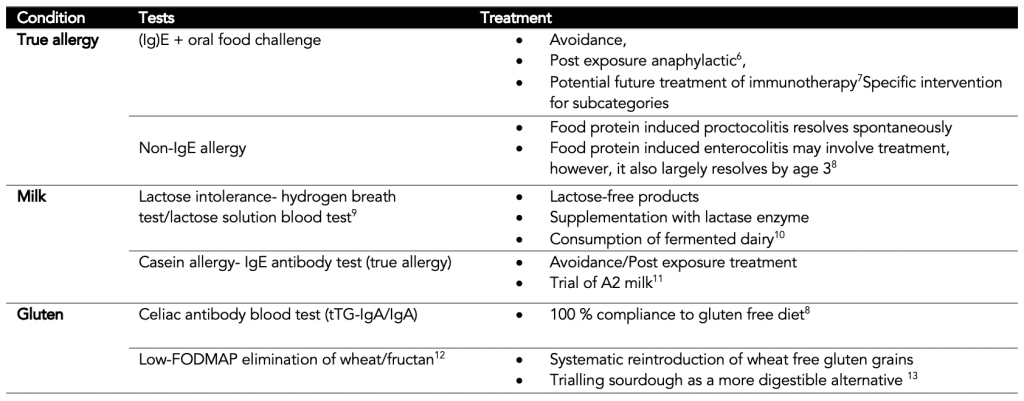

True allergies involve an immune mediated response, which can be broadly categorised as IgE mediated or non-IgE mediated14. This differs from non-immunological intolerances as discussed later. IgE mediated responses often occur shortly after exposure to the allergen and symptoms are caused by an antibody response to the food. The good news is that even with true IgE allergies, a proportion resolve during childhood as the immune system develops; however peanut and seafood allergies tend to persist into adulthood8.

True allergies involve an immune mediated response, which can be broadly categorised as IgE mediated or non-IgE mediated14.

Non-IgE mediated true allergies are less well understood, but in this case the IgE antibodies do not provoke the allergic reaction, although the immune system is still involved15. These allergies largely affect infants in younger childhood and often resolve before the age of 3 – either spontaneously or through treatment.

How Do We Know It’s a True Allergy?

For the IgE food allergies, the test for IgE antibodies (usually via a skin test) in response to an allergen alone is not sufficient as a clinically diagnostic tool14. The sensitivity of the testing is not adequate when taken in insolation, but instead needs to be combined with an oral food challenge (OFC)16. Even though the gold standard OFC test is conducted under double blind placebo-controlled standards, this test is too involved for most clinical environments. Instead, an unmasked version is often used, which is important to remember when considering the accuracy of this test. Still, it is much more reliable than the other, scientifically discounted, yet often used, tests for establishing true allergy. These include kinesiology, hair strand analysis and gastric juice evaluation, all rendered as wholly inaccurate and unreliable8.

Can We Trust Food Allergy Tests?

Unfortunately, some frequently recommended “food sensitivity” tests do not stand up scientifically when it comes to an accurate food allergy diagnosis17. One such test is the IgG test, which is readily available online and often promoted as an easy at home method of establishing food allergies for hundreds of different foods. The test measures the level of IgG antibodies produced in response to various food items. These tests may be accurate at measuring the levels of antibodies present, but presence of IgG antibodies does not equate to an intolerance or allergy18.

Unfortunately, some frequently recommended “food sensitivity” tests do not stand up scientifically when it comes to an accurate food allergy diagnosis.

Instead, healthy individuals will experience some extent of IgG antibody production in response to food; it is arguable that IgG levels actually represent a state of tolerance to food items, after repeated exposure, rather than an immunological aversion to them19. In addition, as we’ve mentioned, other tests that don’t have evidential base include hair analysis testing, applied kinesiology, pulse testing and cytotoxicity20. Sadly, the result of these inaccurate “diagnoses” is often food restriction, sometimes severe in nature21, leading to malnutrition and microbiota deficits22.

IBS vs Gluten Sensitivity?

A common source of controversy in the world of food allergies is gluten, and whether a sensitivity outside of celiac disease exists. There is a definitive test to establish the lifelong condition of celiac disease. If diagnosed, a 100 percent compliance to a gluten-free diet is required, regardless of symptom severity; damage to the intestines is visible during endoscopy and further damage must be prevented23.

The test for celiac involves highly specific and sensitive auto-antibody test, and can be relied upon, unlike the far less concrete realm of non-celiac gluten sensitivity, which is largely discredited scientifically24. However, a reported adverse response following gluten consumption is common25. This is usually gastrointestinal in nature and can instead be attributed to an inability to digest the fructans in wheat (a form of carbohydrate,) rather than an allergy to the protein in gluten26.

Wheat, Not Gluten

This explains why some individuals with IBS type symptoms feel better after reducing or eliminating gluten, usually in the form of wheat. As some evidence indicates that a low-gluten diet may have adverse effects on microbiome health22, (presumably due to individuals having a reduced carb/fiber-rich diet as a result of cutting out most whole grains,) it is worth considering strict restriction of gluten, and perhaps focusing on non-wheat strains or more traditional versions such as spelt, rye etc.

Milk Allergy vs Lactose Intolerance?

Milk allergies are also commonly overestimated27, with the real culprit being lactose, a type of sugar present in milk which up to 65% of the population have reduced capacity to digest due to missing an enzyme (lactase)28. For lactose intolerance, people often find that fermented forms are more digestible10 and individual tolerance levels vary. True milk allergy involves an IgE reaction to casein, a protein in milk products11. Some affected individuals need to avoid dairy altogether and may require post-exposure treatment, but in milder cases some individuals do better with A2 type milk, which has lower casein levels29.

Can We Prevent True Allergies?

Interestingly, pregnant women who consume common allergens during pregnancy may reduce the incidence of allergies in their children30, potentially by pre-exposing and therefore desensitising infant immune systems. However, when the child is born, avoidance of premature introduction of allergens during age 2-3 months may be beneficial31.

One species called P.copri appears protective and, when abundant in pregnant women’s stool samples, not only reduced food allergies but also hay fever33.

Once again, the role of the microbiome is key; pregnant women’s’ microbiome health or lack thereof, may influence their child’s allergy risk32. One species called P.copri appears protective and, when abundant in pregnant women’s stool samples, not only reduced food allergies but also hay fever33. Sadly this strain is often lacking in the west, likely due to antibiotic overuse34. Nonetheless, we can see the value in ensuring a diverse plant fiber-rich diet, brimming with pre- and probiotics during pregnancy to support the creation of a healthy, allergy free child.

Summary

- For a true allergy, we must have an immune mediated response, either IgE or non-IgE in nature.

- Some IgE allergies lessen with age, and non-IgE allergies often resolve by age 3.

- It is important to distinguish between a true allergy to the protein in gluten, from the inability to digest fructans in wheat, in order to avoid eliminations which may detrimentally alter microbiome status.

- When it comes to dairy, it is often the lactose to blame, and traditionally fermented products are better tolerated by many.